Reported by

Kristine Baghdasaryan

Contribution by

Ilia Shumanov,

Kirill Gorlov,

Vlad Netyaev

On-Chain Analysis

Sharad Vyas, OCCRP

Edited by

Grigorii Slobodzian

Fact-checked by

Natalia Korotonozhkina

Illustrations by M.G.

Legal review by

Kirill Gorlov, G.M.

We are grateful for the support and assistance of

Bruno Brandão and Janaína Pavan, Transparency International Brazil, Crystal Intelligence, Elliptic, OCCRP

Some entities and individuals referenced in this investigation, including Bank of China, DBS Hong Kong, J.P. Morgan Hong Kong, Deutsche Bank Hong Kong, Fintech Corporation, Exved, Paysol, Sergey Mendeleev, and Sergey Kunitsa, were contacted for comment or made aware of our reporting. Not all subjects mentioned in the report were reached.

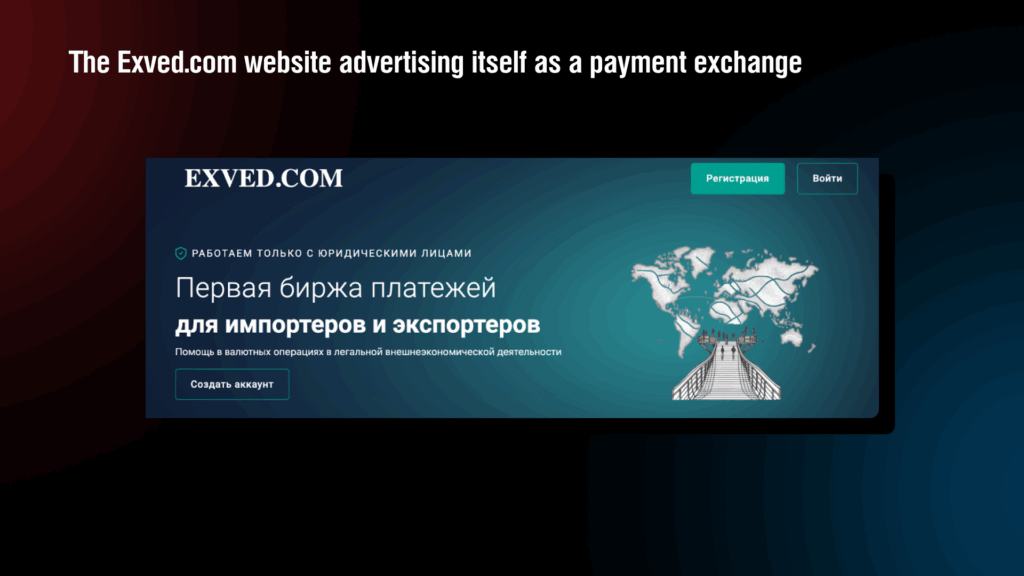

In the evolving ecosystem of Garantex’s successors, Exved surfaces as a “clean” intermediary. It is not a direct clone of Garantex, but rather its operational ghost. It does not advertise itself as a crypto exchange, nor does it inherit the Garantex name. Despite that, it quietly offers the same core promise: to move Russian money abroad, discreetly and without detection.

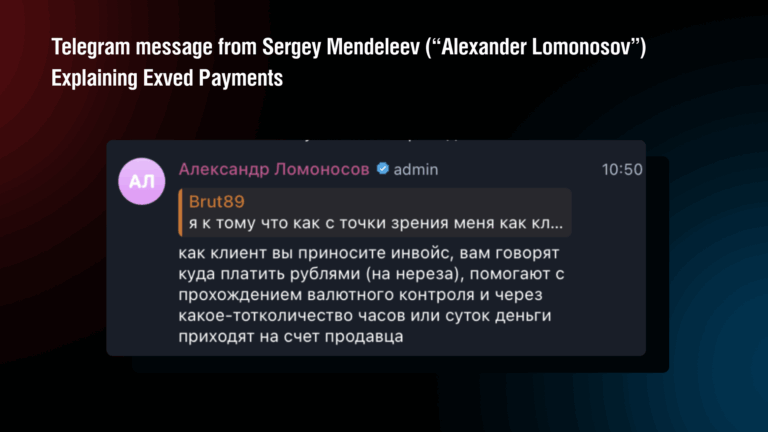

Founded by Sergey Mendeleev, a key figure behind Garantex’s original infrastructure, Exved operates from Moscow-City and presents itself as a legal “payment facilitator.” It offers Russian clients a way to pay in rubles, while their foreign partners receive fiat or crypto abroad. The rubles never formally cross the border, and the exchange takes place entirely outside Russia’s jurisdiction, leaving no visible trace of crypto in the documentation.

On the surface, this model appears tailored to support cross-border commerce. But in practice, it reflects a deeper transformation in Russia’s financial architecture – one that increasingly blurs the line between formal legal transactions and covert sanctions evasion.

OFAC accused Exved of facilitating “cryptocurrency-mediated trade between Russia and other countries to subvert U.S. sanctions on Russia’s financial services sector”. On top of that, the platform is used to facilitate trade in dual-use goods. At the same time Exved is not a classic laundering network, but a system where weak KYC standards and opaque intermediaries allow potentially high-risk transactions to pass under the radar. Platforms like Exved enable clients to pose as shell companies and shift money under the guise of legitimate trade.

Some entities and individuals referenced in this investigation, including Bank of China, DBS Hong Kong, J.P. Morgan Hong Kong, Deutsche Bank Hong Kong, Fintech Corporation, Exved, Paysol, Sergey Mendeleev, and Sergey Kunitsa, were contacted for comment or made aware of our reporting. Not all subjects mentioned in the report were reached.

All cited chats and calls were conducted in Russian; quotes are translated without altering meaning.

How to pay for dual-use goods through shell companies and cryptocurrency easily and quickly, while bypassing customs and sanctions restrictions?

This was not just a question, it was an offer we received from Exved. The company promised to help solve complex issues with payments, paperwork, and transfers where formalities and rules take a back seat. No excessive checks or meetings, just fast solutions that keep clients out of sight of banks and regulators.

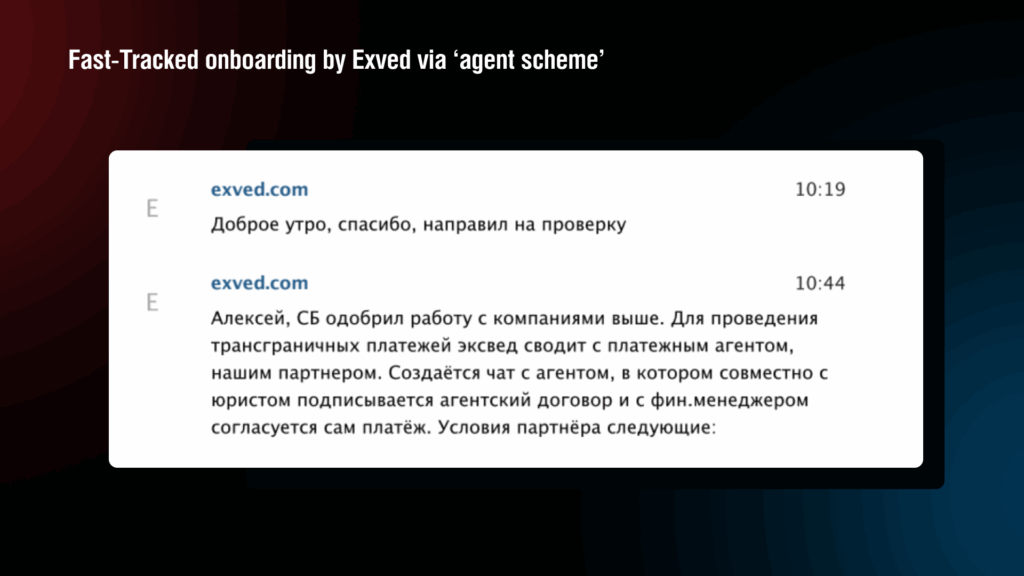

In October 2024, posing as a non-existent Hong Kong-based electronics exporter, our team contacted Exved via its public Telegram account. Exved asked for a simple “company card” for the Hong Kong entity and Russian counterparties. 25 minutes after acknowledging receipt of files, Exved replied that its security team had “approved” us and moved us into a group chat with its payment agent.

At this stage, we saw no evidence of a background check on the Hong Kong company: no request for corporate documents beyond the basic card, no beneficial-owner details, no IDs, only what looked like a lookup of the tax numbers of the Russian companies.

Exved’s website claims clients must undergo a full identification procedure in line with 115-FZ (Russian AML/CFT law) and, in some cases, KYC/AML for foreign counterparties. Even if Exved or its agents were in fact required to comply with the 115-FZ, our onboarding fails to comply with it.

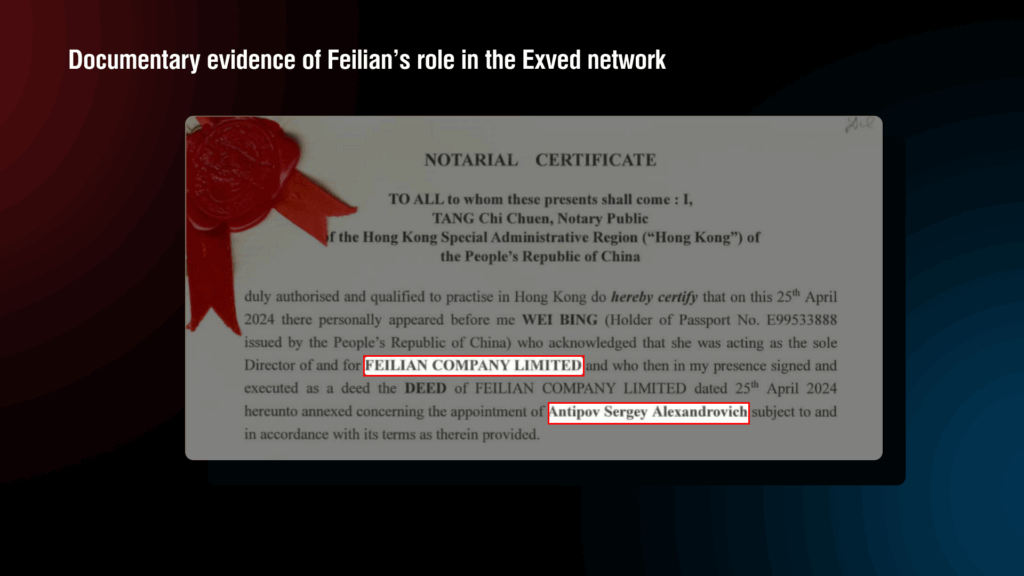

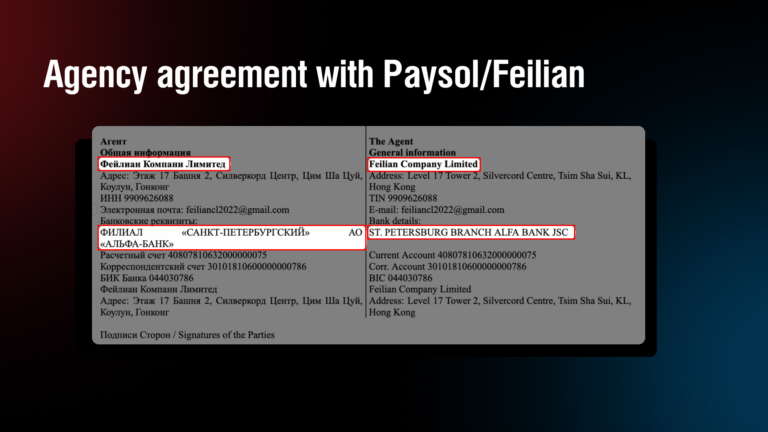

The Exved representative explained that transactions would be handled through ООО “Platezhnoe Reshenie” (Paysol LLC) a legal entity registered in Russia that acts as Exved’s “agent.” However, we were soon told that the actual agency agreement would be signed not with Paysol, but with Feilian Company Limited, a Hong Kong-based firm formally owned by a Chinese individual but represented under power of attorney by a Russian national, Sergey Antipov.

The arrangement worked as follows: our fictional Russian importer would transfer rubles to Feilian’s Alfa-Bank account in Russia. The Hong Kong-based entity, Feilian, would then convert and forward the money to our fictitious Hong Kong-based exporter in dollars, yuan, or USDT.

Clarifying note: ► Show details

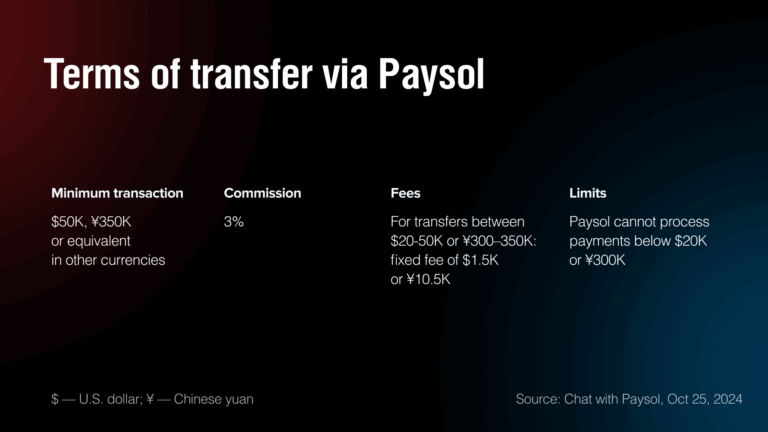

It has an apparent contradiction. We keep a literal translation of the message. We read it as establishing two thresholds: (1) a standard minimum of $50,000/¥350,000 with a 3% commission; (2) a lower band of $20,000–$50,000 / ¥300,000–¥350,000 with a fixed fee of $1,500 or ¥10,500. Transfers below $20,000/¥300,000 are not processed.

“We have plenty of clients, Russian importers, who bring in dual-use goods from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Telecommunications, microprocessors… We're talking about multimillion-dollar annual volumes, and so on.”

– Call with Paysol, Oct 22, 2024

Paysol assured us that all funds would be protected by an agency agreement signed before transfers. The draft agreement named Feilian would function as the agent authorized to execute cross-border payments, using vague language that masked the true nature of the transaction, framing it as a general financial service rather than a crypto conversion.

“We will conclude an agency agreement with you… This is a completely legal format. We receive rubles in our account and then pay your foreign partner in the needed currency. We offer several options: USDT, dollars, yuan – just tell us which one you prefer.”

– Chat with Paysol, Oct 2024

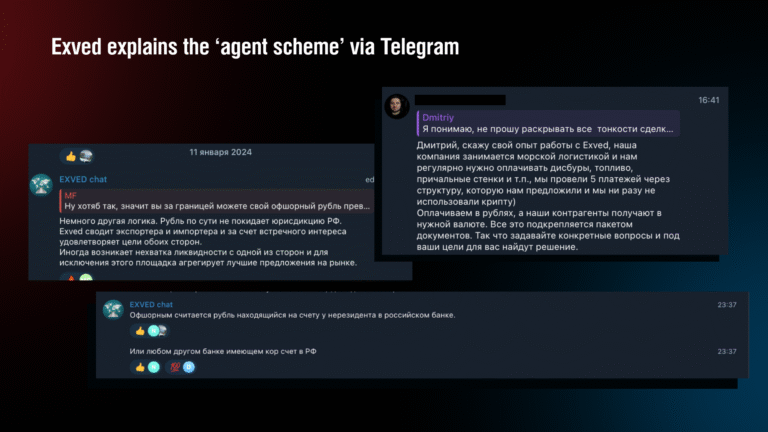

When asked for technical details, the agent explained the dual-circuit structure of Exved’s so-called “agent-based scheme”. Domestically, payments are made in rubles to a Russian bank account held by the foreign-registered agent company (such as Feilian). Russian banks see this as a legal domestic payment linked to a foreign invoice. The foreign leg of the transaction is handled separately, with no mention of Russia or rubles, using offshore*Here, the term “offshore” is not used in the narrow tax sense. Instead, it follows the broader compliance and IMF usage, meaning financial centers outside the client’s home country that provide large-scale services to non-residents and international transactions. Hong Kong and Dubai, for example, are considered offshore jurisdictions in this sense, even if they are not traditional “tax havens.” accounts in jurisdictions like Hong Kong, Dubai, or Thailand.

Critically, all crypto activity remained behind the scenes. In conversations, Exved stressed the importance of secrecy:

“The client submits a payment order under the agency agreement without indicating that the payment will be made in crypto – it is presented simply as a currency transfer. The contract makes no mention of crypto. No bank will know. It is visible only between us.”

– Chat with Paysol, Oct 13, 2024

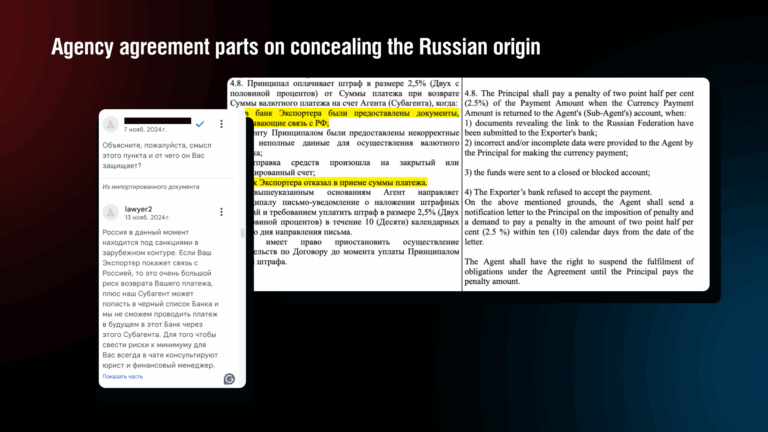

To minimize exposure, Exved requires exporters to hide any Russian connection. Clause 4.8 of the agency agreement prohibits clients from presenting any documents that mention Russian involvement. As the agents warned, if the Russian link is exposed, foreign banks might reject payments and blacklist their sub-agents. Lawyers and financial managers from Exved assist clients in preparing “clean” contracts and invoices to obscure Russian origins, ensuring streamlined processing.

The scheme is designed to maintain plausible deniability for clients. Rubles are paid into a Russian bank account tied to an intermediary, while the corresponding foreign currency is issued from an offshore account in jurisdictions including Dubai, Hong Kong, Thailand and EU. The intermediary takes a fee but, more importantly, ensures that the origin and destination of funds remain disconnected on paper. This deliberate separation creates a structure where neither the sender nor the recipient is directly visible to regulators, making the system appear clean.

The entire method relies on the legally worded veil of agency that conceals the true economic nature of the transaction. The underlying operation (a crypto-backed cross-border transfer) is never disclosed in contracts or instructions. The transaction appears in Russian banking systems as a domestic payment for services under the agency agreement and, on the receiving end, as a clean wire from a third-party intermediary.

Formalized in Moscow and crypto-processed offshore, this arrangement offers Russian firms a legal fiction: compliance on paper, circumvention in practice.

Exved’s financial flow can be visualized as a network of shell companies, crypto liquidity pools, and rotating banking channels.

“For each payment, a payer is selected individually based on the request you send in the chat. We use different jurisdictions: Hong Kong, Thailand, the UAE.”

– Chat with Paysol, Nov 2024

While Exved has referenced working with multiple jurisdictions for payouts, including Hong Kong, Thailand, and the UAE, holiday notices and platform logs also mention activity linked to the U.S., Turkey, and Indonesia, suggesting these may be among the supported destinations for transfers, even if they are not confirmed locations of registered intermediaries. This diffuse and modular structure allows Exved to shift routes quickly and avoid detection, all while leaving rubles technically inside the Russian banking system.

When asked what would happen if a foreign bank rejected the international leg of the transaction, Exved’s representatives reassured us that this was not a serious problem. In such cases, they said, the payment is simply rerouted through a different agent or bank. This explanation aligns with the agency agreement, which allows for such rerouting in case of failed transactions.

"…we simply choose another agent or switch the bank… It's a working setup."

– Call with Paysol, Nov 2024

Exved uses a multi-step process to move money internationally while obscuring the trail, keeping the crypto element invisible to regulators and banks. Internally, this method is known as the “agent scheme” (агентская схема). A typical Exved-facilitated payment works as follows:

Most likely a formal or even simulated KYC: we managed to pass the procedure by providing documents of a fictitious company.

The Russian importer signs an agency agreement with a foreign intermediary (in our case, the Hong Kong-based company Feilian), introduced by representatives of Paysol, Exved’s agent.

Rubles are transferred to the Russian bank account of offshore intermediaries in Russia, creating the appearance of a domestic transaction.

The offshore agent conducts the foreign currency transfer, either in fiat or USDT, to the foreign supplier. Crucially, cryptocurrency is never mentioned in the Russian documentation, shielding the operation from financial intelligence scrutiny.

“We’ve selected banks that don’t ask unnecessary questions. They’re indifferent. And even if someone inquires, the questions come to us – not you.”

– Call with Paysol, Oct 16, 2024

When discussing how Exved facilitates the foreign leg of its cross-border transactions, its agents revealed a careful selection of financial institutions that can handle payments in fiat or USDT. While none of these banks were explicitly described as partners, they were presented as “working banks” (“рабочие банки”) – institutions that have been used frequently and successfully, albeit not without occasional compliance issues.

Hong Kong has emerged as a key jurisdiction. Banks like J.P. Morgan HK, Deutsche Bank Hong Kong, DBS HK, and Bank of China were cited as frequently used but occasionally problematic conduits.

Exved agents emphasized that despite these challenges, payments “pass through these banks repeatedly, literally every day.” Their experience, they said, comes down to understanding “which jurisdictions and intermediaries to use” to avoid disruptions.

“We work with Russia’s biggest banks every day… they don’t care.”

— Call with Paysol, Oct 16, 2024

Notably, Exved also described Russian banks that are aware of and accept ruble-side operations under this system. They named T-Bank (Т-Банк) and Expobank (Экспобанк) as examples of domestic institutions that permit settlements referencing digital assets, even when the underlying transaction involves USDT.

At no point did the Exved team claim these banks were complicit. Instead, they suggested that the documentation (consisting of agency contracts, invoices, and settlement records) was structured in such a way that “questions rarely arise,” even when the underlying transfer involved cryptocurrency. Still, this amounts to a gray-zone workaround, relying on compliant paperwork to obscure the true flow of funds. The transaction mimics legitimate international commerce while avoiding scrutiny tied to crypto or sanctions enforcement.

In an audio call with Paysol’s legal team, we also asked directly whether their services could be used for sensitive cross-border shipments, including dual-use goods such as microprocessors. The response was measured but revealing.

Tatiana, a compliance officer working with Paysol’s legal team, did not outright confirm that Paysol itself manipulates customs declarations. However, she acknowledged that the scheme is commonly used to facilitate the import of restricted goods, particularly from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan:

“We have plenty of clients, Russian importers, who bring in dual-use goods from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Telecommunications, microprocessors… We're talking about multimillion-dollar annual volumes, and so on.”

– Call with Paysol, Oct 22, 2024

When pressed on how these transactions are structured to avoid detection, Tatiana emphasized the importance of tailored documentation and logistics partners:

While she stopped short of admitting direct involvement in falsifying documents, her comments suggest that Paysol and its intermediaries routinely facilitate trade in dual-use items by navigating around banking scrutiny and customs oversight.

Exved and its network do not directly forge documents. Rather, they enable and process payments based on sanitized invoices that may not reflect the actual goods. While the potentially sensitive or sanctioned nature of the goods may differ from what is listed, this approach is primarily designed to avoid raising red flags with foreign banks involved in the second leg of the payment chain. Russian banks, according to the agents, often turn a blind eye to such discrepancies in product codes, especially for dual-use goods.

Not every transaction facilitated through the system is illegal per se, but the structure is flexible enough to accommodate both legitimate trade and deals designed to bypass compliance checks, including those involving sanctioned goods or jurisdictions.

Because Exved operates without a legal entity, as Sergey Mendeleev acknowledged himself, the platform’s face necessarily shifts to proxies. In Russia, as we demonstrated above, that role is filled by Paysol.

At the center of Paysol’s domestic operation is Sergey Kunitsa – CEO of Paysol and former head of RMA Logistics, a customs brokerage firm in liquidation that once participated in Russia’s “green corridor” fast-track import program.

Kunitsa notably owns plots of commercial land in Moscow-City, where Exved, Paysol, and Garantex are located.

Considering that RMA Logistics had representative offices in several cities in China and Germany, Kunitsa presumably could use his preexisting business networks to transform Paysol into Exved’s legal buffer, able to simulate domestic legality while enabling grey trade.

We asked Paysol to run a dummy transaction to test the mechanism. They provided a crypto wallet address. Crystal Intelligence and Elliptic analysis showed that this wallet had previously received funds from a Garantex Europe address listed in U.S. and EU sanctions datasets. This on-chain link reveals that the same network is still able to bypass international sanctions, now operating under new names like Exved and Paysol. The finding underscores the risks in Russia’s crypto policy and the threat it poses to the stability of the global financial system.

The wallet in question had processed over $112 million in total inflows and outflows across 518 transactions. Among the counterparties was Garantex Europe OÜ, a company sanctioned by the OFAC in April 2022. On December 25, 2024, the wallet received $234,366.39 from a Garantex-associated address. Less than a month later, on January 17, 2025, $2.66 million was transferred from the same wallet to what we had identified as Paysol’s operational wallet – the same one provided to us during onboarding.

Even more concerning was a second leg in the chain: smaller amounts later flowed back to a wallet tied to Garantex Europe, suggesting possible circular layering – a known method of obscuring transaction origins in laundering operations.

Further investigation according to Elliptic revealed additional troubling connections. The wallet of Paysol also showed indirect exposure to:

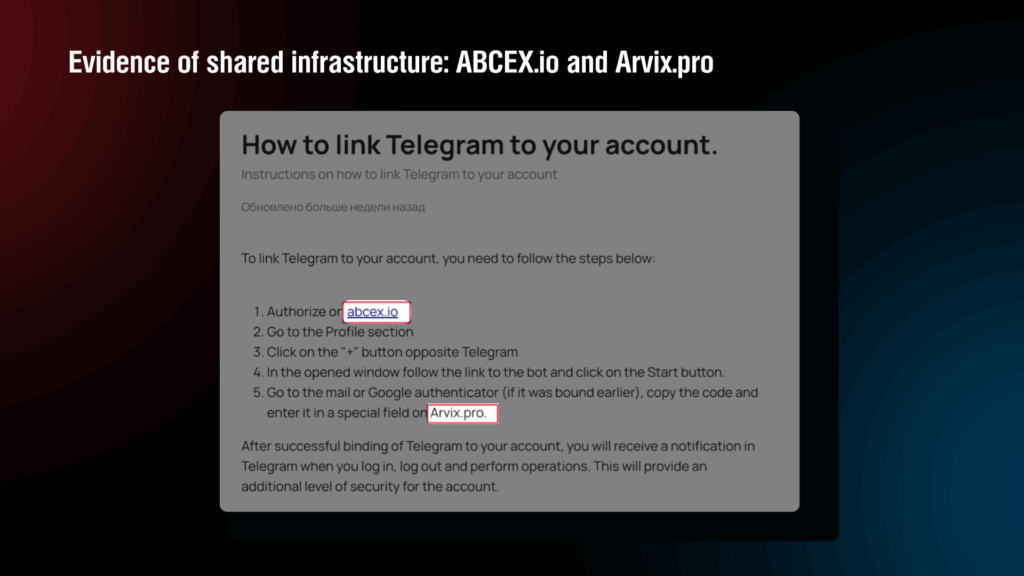

Using Crystal blockchain analytics, we identified a transfer from Arvix.pro* Arvix.pro is a Georgian entity Arvix LLC registered in 2023 and located in Tbilisi, Georgia and operating through some Georgian nominals and intermediaries. We found that Abcex LLC registered in Georgia in 2023 at the same address: 264 Omar Khizanishvili Street, Tbilisi Technology Park FIZ., an entity identified as the same as abcex.io** ABCEX, the exchange behind Arvix.pro, is a cryptocurrency platform that we believe to be associated with Sergey Mendeleev — founder of Exved and a key figure behind Garantex’s original infrastructure., to our target wallet. In November 2024, Arvix.pro sent 60,000 USDT to an intermediary address (Wallet A). That wallet then forwarded 1,040,090 USDT to our target wallet (TPZAs5jY…).

Notably, this same intermediary wallet (TWwm9Qba…) was also used in a separate transaction on the same day, when $2.66 million was routed from a wallet linked to Garantex Europe to the same target wallet. Because this intermediary wallet both received and sent funds involving Garantex-linked addresses, it appears to be part of the same transaction infrastructure.

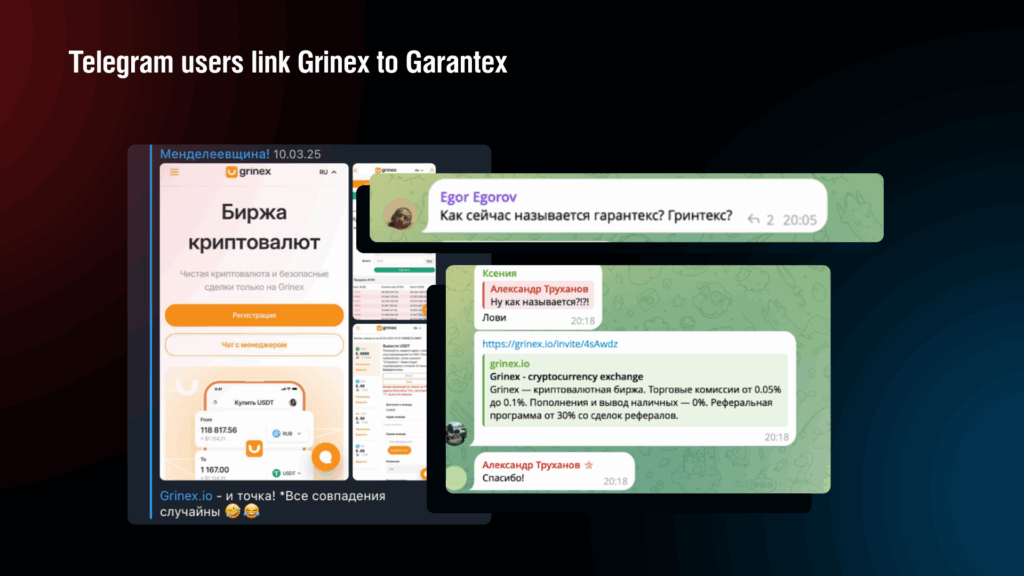

Based on the Crystal Intelligence, Arvix.pro, which has been linked to abcex.io, appears to serve as a transactional bridge between Garantex’s sanctioned legacy and Grinex’s rebranded architecture.

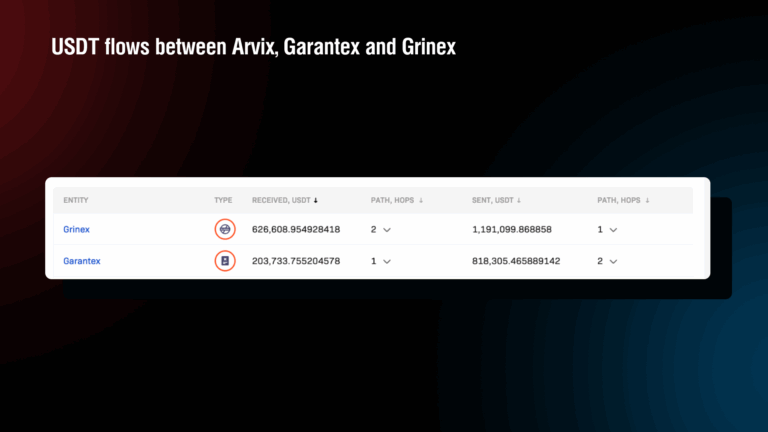

The data reveals a dynamic financial interplay between Arvix.pro (ABCEX), Garantex, and Grinex, reflecting a continuous flow of USDT across these interconnected entities.

Garantex sent approximately 818,305.47 USDT and received 203,733.76 USDT, with transactions spanning 1–2 hops.

Grinex sent a larger amount: approximately 1,191,099.87 USDT and received 626,608.95 USDT, with flow paths of 1–2 hops.

The movement of over 2 million USDT in total across all channels in both directions show the repeated interactions, indicating that ABCEX may be acting as a liquidity router or buffer between the two exchanges.

The analysis of the wallet provided by Paysol for our test transaction revealed connections not only between Exved and Garantex, but also with other branches of the same ecosystem, including Grinex and ABCEX. The infrastructure, terminology, and operational methods closely mirror practices previously employed by Garantex. While Grinex appears to continue Garantex’s legacy under a new name, Exved operates as a successor system optimized for legal ambiguity – a next-generation crypto workaround rather than a direct clone. Transaction flows and wallet linkages suggest the network’s continued activity behind new fronts. Taken together, the blockchain data, recorded calls, and supporting documents indicate a clear continuity of methods and objectives.

Behind the complex architecture of crypto wallets, offshore transfers, and sanctioned counterparties lies something deceptively simple: Telegram. Not a regulated exchange or a licensed portal – just a messaging app. Yet this is where it all happens: onboarding, contracts, wallet addresses, even KYC is all run through chats and bots in a gray-zone ecosystem that operates largely out of sight.

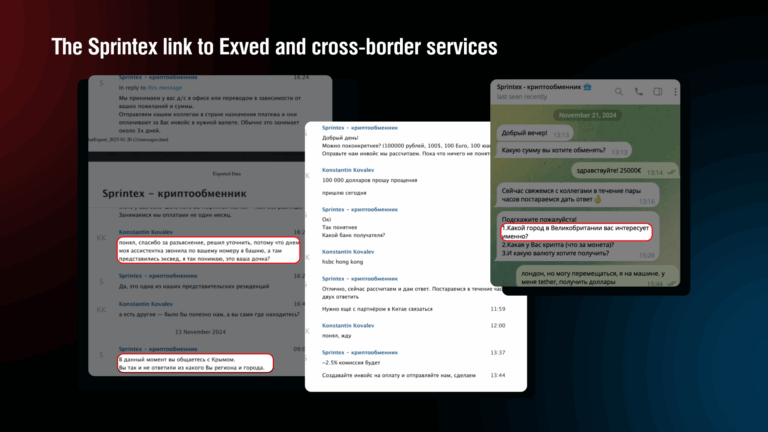

Telegram serves as Exved’s sole operational interface. Along with Exved, firms like Sprintex and ABCEX also operate this way. These platforms share contacts and Telegram bots and are registered to the same physical zones in Moscow-City.

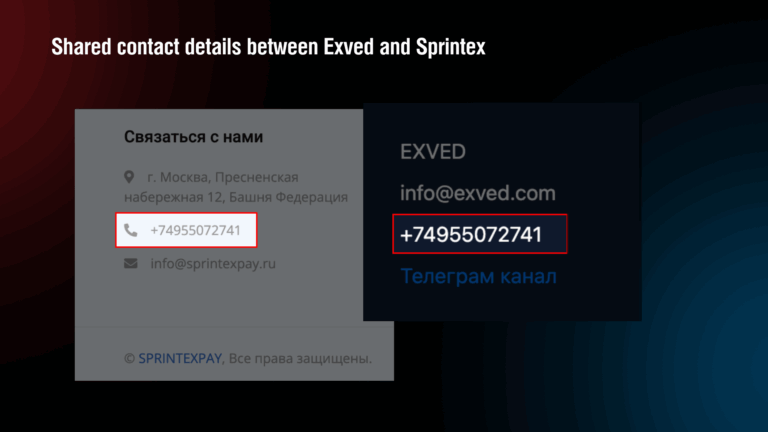

Sprintex (previously SprintexPay) and Exved share the same phone number. Sprintex earlier represented itself as the first payment service for importers and exporters and offers assistance in international transfers for legal foreign economic activity.

Now Sprintex offers USDT operations within Russia, Georgia, and the United Kingdom, as well as in annexed Ukrainian territories (Crimea, Mariupol). Together with Exved, these entities exploit Telegram as their primary operational platform, bypassing conventional compliance procedures such as formal KYC portals or regulated platforms.

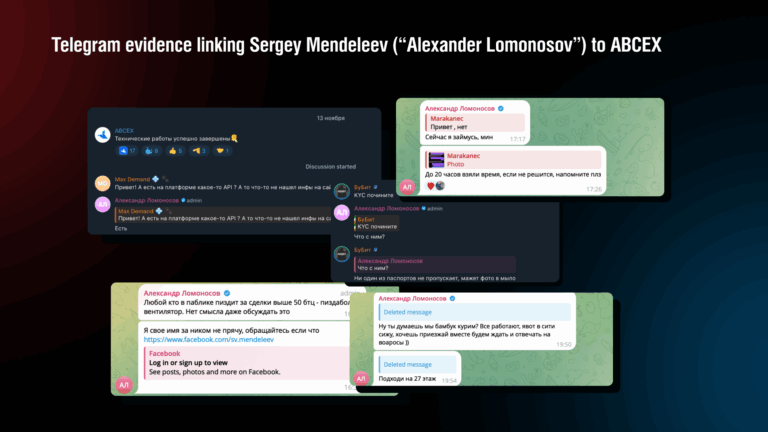

Exved’s network appears to extend to ABCEX, a cryptocurrency platform that we believe to be associated with Sergey Mendeleev. While Mendeleev has publicly denied founding the platform, a Telegram user named “Lomonosov” has for years handled customer support and technical queries across projects tied to Mendeleev in community chats and in ABCEX’s official Telegram group. In one exchange, the user explicitly wrote that he is Sergey Mendeleev and that he “does not hide behind the nickname.” Based on this long-standing pattern of operational involvement and self-identification, we conclude that Mendeleev is likely a key figure behind ABCEX’s management, if not its direct owner.

This connection underscores a pattern of coordinated financial operations within Moscow-City, where over 20 exchanges operate by exploiting regulatory loopholes and legal ambiguities. Telegram, rather than traditional operational infrastructure, serves as their primary platform, highlighting a shift in how illicit financial ecosystems function in the digital age.

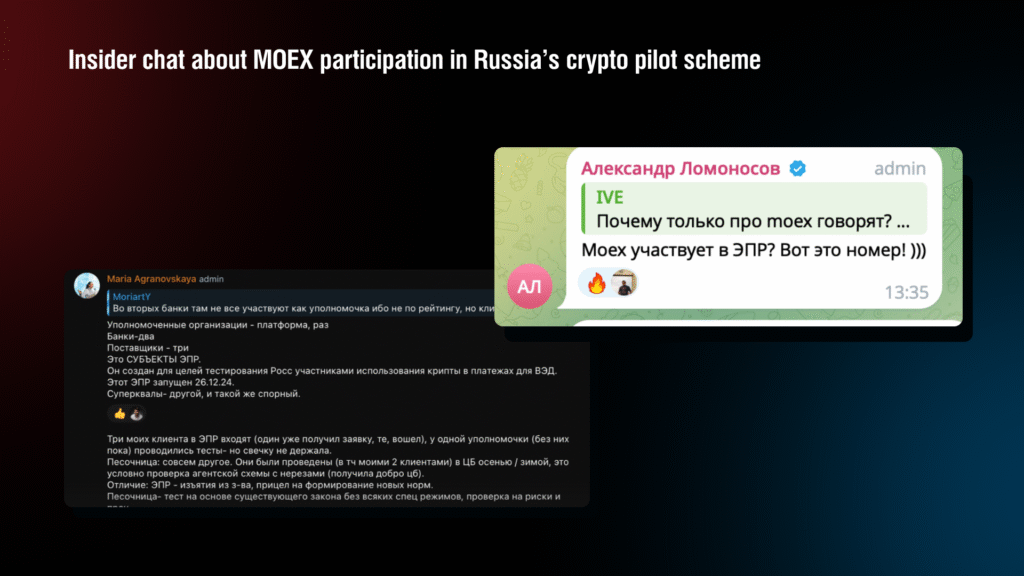

Officially, the Bank of Russia has not yet publicly launched the regulatory experiment. By law, the ELR must be established by a public Bank of Russia act approving an ELR programme that specifies participants and special rules. No such act or programme has been published to date. However, according to blockchain lawyer Maria Agranovskaya, a close partner of Sergey Mendeleev, closed pilot phase testing began as early as December 2024 with a limited set of participants in violation of the law.

Bloomberg reported that if successful, the pilot may pave the way for cryptocurrency trading platforms operated by the Moscow Exchange (MoEx) and the St. Petersburg Currency Exchange in 2025.

According to Sarkis Darbinyan, cofounder of Roskomsvoboda, the story of Exved and crypto regulation in Russia is a continuation of long-standing gray-zone practices that date back to BTC-e and WEX. These schemes are now being tailored for importers and exporters, but fundamentally, nothing has changed. The state is not interested in legalizing the crypto market: if not for the need to circumvent sanctions, this sector would have been shut down long ago. Over the past ten years, no basic rules for buying, selling, or exchanging cryptocurrency have been introduced, which shows the authorities do not want such companies to operate in the legal market.

“The Experimental Legal Regime is a closed system for select major players; if implemented, regulation will come with a high entry barrier, mainly for state banks and brokers. For the mass market, such schemes will remain inaccessible. The state uses cryptocurrency solely as a tool for sanctions circumvention and settlements with friendly countries, not for technological or market development. Any attempts at legalization outside the ELR will face strict limitations and risks, including criminal and administrative liability. The development vector is toward a digital ruble and tight control, not an open crypto market.”

According to Artem Tolkachev, a legal expert specializing in digital assets, Russia’s approach to crypto regulation is based on restriction and control, not market development.

“Agency schemes for cross-border crypto payments have existed for years and continue to operate in a legal gray area, as the government resists full legalization. The new Experimental Legal Regime is a closed system for select companies and will not change the situation for most market participants, who will remain in the gray zone. Russia ignores successful models from neighboring countries and instead simulates regulation without providing real legal tools for business. As a result, crypto flows stay underground, and the state misses out on tax and innovation opportunities. The only effective path would be to legalize crypto, remove excessive barriers, and focus on regulating fiat on/off-ramps, not total control.”

Ultimately, the shift from evading sanctions to promoting financial innovation symbolizes a significant change in Russian statecraft, carrying major implications for the global sanctions framework. According to reports from Bloomberg, Russia has actively sought to adopt these alternative infrastructures, circumventing traditional financial mechanisms. This experimental regime may lay the groundwork for state-approved crypto exchanges, including those affiliated with previously sanctioned companies such as Garantex.

While the Bank of Russia officially “does not disclose participants,” documents and expert analysis suggest this scheme institutionalized operations already perfected by entities like Garantex and its spin-offs.

According to a document obtained by Transparency International Russia, the Bank of Russia confirmed that:

“In light of sanctions-related risks, the Bank does not disclose participants, volumes, or platforms involved in the experimental regime.”

Despite the BoR’s formal anti-crypto stance, First Deputy Chair Vladimir Chistyukhin admitted that cryptocurrency is no longer a whim but necessary, especially for Russia’s export-dependent economy under sanctions:

“We must do everything to keep the wheels turning.”

How the system may work: While the Bank of Russia has not disclosed precise details, available information and expert commentary suggest the Experimental Legal Regime may operate through a three-tiered model: authorized banks, authorized platforms (trading venues), and liquidity providers. Under this structure, major exporters and importers apply through their servicing banks, which in turn interact with designated crypto platforms and liquidity suppliers. These suppliers, whose sourcing methods remain opaque, are expected to provide crypto to banks, which then facilitate international transfers for clients. Bloomberg reported that for initial trials, Russia was going to use the infrastructure of the National Payment Card System (NSPK) to conduct exchanges between rubles and crypto, offering a state-regulated alternative to SWIFT-like systems. While the Bank of Russia has not confirmed the results, these trials have likely already been conducted, according to sources familiar with the matter.

“To participate in the Experimental Legal Regime (ELR), interested parties may submit a formal request to the Bank of Russia.”

– Central Bank

Within this gray regulatory framework, structures associated with Garantex, including projects like Exved, have developed similar mechanics for cross-border crypto payments that operate in legal limbo. While there is no confirmed evidence that these systems directly influenced the design of Russia’s Experimental Legal Regime (ELR), there are signs of regulatory awareness. According to Exved CEO and founder Sergey Mendeleev, the platform’s internal mechanism was reviewed and approved by both the Bank of Russia and Rosfinmonitoring prior to regulatory experiment legislation in 2023.

Nevertheless, several tools employed by Exved, such as ruble-linked tokens and offshore USDT settlements, closely mirror the financial mechanisms that Russian regulators are now cautiously exploring under the forthcoming Experimental Legal Regimes (ELR). Although the experiment was legally authorized in September 2024, it has not yet been formally launched. According to Agranovskaya, what currently exists is a “closed pilot phase” involving a handful of preselected participants.

While platforms like Exved are not officially authorized, their tolerance by regulators once hinted at a de facto public-private partnership. Yet recent steps by the Bank of Russia, including proposals to license crypto platforms and define “qualified investors” suggest a shift toward tighter control. Rather than ignoring crypto activity by trusted actors, the Russian government now appears to be building a centralized framework that could eventually marginalize or absorb decentralized alternatives like Exved.

Exved’s emergence in the aftermath of Garantex’s takedown underscores the remarkable resilience and adaptability of this illicit financial infrastructure. Far from eliminating the threat, the crackdown forced an evolution: Garantex’s laundering operations have been effectively reborn through Exved’s covert model. This “ghost successor” carries forward the same core mission: moving Russian funds abroad discreetly, while deftly exploiting regulatory blind spots at every turn. The result is an offshore, state-tolerated architecture that continues to subvert international sanctions regimes and challenge the efficacy of traditional enforcement measures.

Exved exemplifies a new breed of decentralized crypto-laundromat that blurs the line between legitimate commerce and illicit transfers. It operates through a web of shell companies and intermediary accounts, formalized in Moscow but executed offshore, and is coordinated via encrypted, Telegram-based channels rather than any transparent exchange platform. By leveraging weak KYC standards and legal facades, Exved’s agent-driven scheme enables high-risk payments to masquerade as routine trade transactions. This agile, modular design – switching banks, jurisdictions, or corporate fronts as needed – allows the network to reroute around obstacles and avoid detection. Such an arrangement marks a fundamental shift from centralized, easily-targeted exchanges to distributed networks embedded within regular financial flows, rendering conventional jurisdiction-bound controls increasingly ineffective.

A critical consequence of Exved’s covert model is the erosion of financial oversight. Transactions are structured to leave no crypto footprint in Russian banking records, and the underlying cryptocurrency conversion remains hidden behind agency agreements and offshore layers. By keeping the crypto element “behind the scenes” and only showing fiat payments between proxies, Exved strips regulators and banks of the transparency needed to spot illicit flows. In effect, it creates a legal fiction of compliance on paper while audit trails disintegrate.

Despite its low profile, Exved is deeply interwoven with Garantex’s ecosystem. Founded by Garantex’s own architects, it operates from the same Moscow-City hub and taps into the prior exchange’s liquidity pipelines. Blockchain traces confirm that Exved-linked wallets interact with Garantex’s sanctioned addresses and its rebranded offspring like Grinex – often via obfuscation hubs such as the mixer ABCEX/Arvix. These on-chain linkages prove that the ostensibly new platform is in fact drawing from a common illicit liquidity pool. In essence, Garantex’s network never disappeared; it simply reconstituted itself under new names and legal veneers, with Exved orchestrating the domestic end of this transnational laundromat.

Notably, Exved’s operations extend beyond financial maneuvering into facilitating sanctioned commerce. The company’s willingness and capability to finance dual-use goods imports (for example, covertly purchasing microelectronics from China and Hong Kong) illustrate how this network directly undermines international security controls. By sidestepping banking checks and customs scrutiny through carefully tailored documentation, Exved enables Russian clients to acquire sensitive technologies that would otherwise be restricted. Our undercover interactions with Exved’s agent, Paysol, confirmed that this scheme is commonly used for dual-use goods transactions. Such deals, cloaked in sanitized invoices and creative customs codes, are not outliers but rather standard practice. This means the harm inflicted by Exved’s crypto-laundering network goes beyond financial crime – it becomes a direct threat to global security, allowing sanctioned states or actors to clandestinely procure critical dual-use components.

In sum, Exved’s continuation of Garantex’s blueprint epitomizes the challenge facing international regulators and law enforcement. Traditional tools – from entity-based sanctions to bank-centric oversight – are ill-suited against a shape-shifting web of offshore proxies, encrypted platforms, and opaque transactions. Confronting this new paradigm will demand unprecedented global coordination and innovative strategies. Without a concerted update to regulatory and enforcement approaches, networks like Exved’s will continue to erode the integrity of the international financial system and empower the evasion of laws.